Bianca & Sons

Craftsmen's technologies

Weronika and Marco are an international couple who in 2013 decided to risk it all and go live in the rural Monferrat, Italy, countryside. They mostly create wood and clay objects for everyday use in the home and kitchen and sell them on the Internet.

Weronika majored in Italian during her Erasmus exchange programme, while Marco majored in Philosophy, at the University of Turin, where he also worked, though in the field of information technology. He would often visit a carpentry shop to learn how to restore furniture, as his grandfather had been a carpenter and passed on to him his passion for woodworking. Eventually, Weronika completed her studies and Marco quit his job, and both embarked on a yearlong journey around the world (especially India and East Asia), mainly to clear their heads and figure out what they wanted to do in life. Marco enjoyed working with wood, and Weronika became passionate about it as well just watching him restoring furniture. And so, they asked themselves, "Could we survive creating wooden bowls and chopping boards?".

When Marco was a little boy, his family bought a house in the countryside, not far from Turin, where they kept a vegetable garden, while Weronika's parents kept a wooden cabin that was built by her grandfather in the woods outside Warsaw. This shared rural experience helped drive them away from the city and toward life in the country. And do it right away. Because the common idea of going about it one step at a time – first buying a country cottage, then over the years fix it up and, finally after retiring, enjoying it – did not appeal to them at all. It meant living their entire life in the city holding jobs they didn't like. They first dove into the unknown by going to live in the countryside, and then again by beginning to create wooden products and selling them online. It went pretty well. Actually, very well. Today they sell almost exclusively to customers outside of Italy, most of them from the United States.

How did you adjust to living in the country?

Weronika: "It was quite difficult in the beginning, because we approached country life with the mentality of city denizens. We knew very little about it, and you can't learn much about cultivating a vegetable garden and orchards, raising sheep and hens from books alone. And on top of that, we had to learn a profession. But we liked it right from the beginning, because – despite suffering huge losses – we had always gotten something back from our work and effort: fruits, eggs, or walks in the woods with our dog, Bianca. In fact, she gave our company its name."

Where did the decision to work with wood came from?

Marco: "I had worked as furniture restorer in the past and loved it. Unfortunately, during the 2009 economic crisis, practically all restorers operating in our area closed down, and so I thought I'd better change direction but still work with wood."

When did you begin using woodworking machines and how did it go?

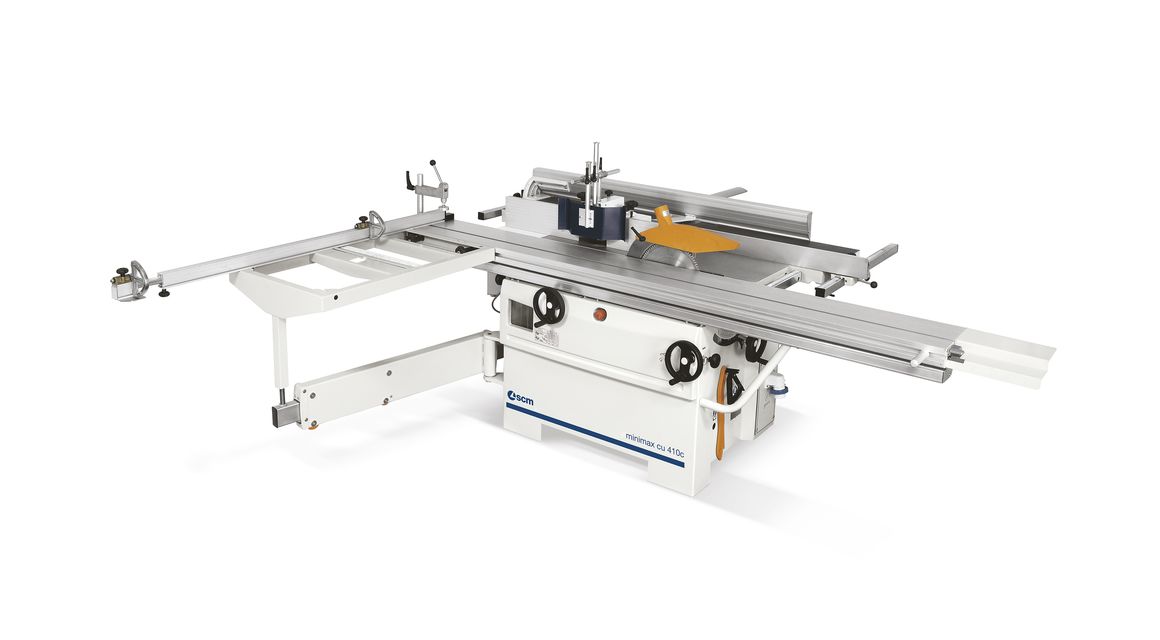

Marco: "We were intent on getting certain results with our products and we knew we could reach such results sooner if we worked full time rather than as hobbyists in our spare time. We had a terrible experience in the beginning with a used machine we bought which had a defect we had not been able to spot inspecting its exterior, but that caused it to work poorly. After a year of trying to figure out where we had gone wrong with its settings, we concluded that it had most probably fallen down and consequently had a damaged flat table and skewed settings. And so, we bought a new machine, a small combined SCM Minimax model. That past experience had helped us understand how fundamental a machine precision is to doing things well. Money saved on an initial investment is actually money lost. We have followed this philosophy ever since, with all the machines we have purchased."

Your products are meticulously handcrafted. Do you think that shops like yours could benefit from woodworking machines with a greater level of automation?

Weronika: "When a machine comes with too much automation, you rule out a certain type of woodworking and lose what distinguishes handcrafted products from industrial products, with which we can't compete. This means that it is essential for us to use machines that offer the carpenter a certain level of freedom. Greater automation = lesser creativity, less craftsmanship; it means stripping the handcrafted product of its very nature."

Your products are mainly kitchenware which come in contact with food. What kind of finishing do you give products to ensure their durability and compatibility with food?

Marco: "Initially we used Vaseline oil. But not having real substance, it lasted little. In addition, we didn't like the fact that the finish was short-lived, intended only to attract buyers but no longer existing by the time products were actually put to use in the kitchen. We switched therefore to raw linseed oil – a Swedish product we buy through a German website. Four-five coatings provide a good finish that successfully withstand washing with a sponge under warm water. Recently we discovered in a book by Tad Spurgeon, an American painter, a number of formulas for improving the quality of commercial linseed oil by employing purification procedures used by 16th- and 17th-century painters and string instruments makers. We've been testing them, but it's still too early to report any definite results.

You have your own website but you use the services of another platform (etsy.com) to sell your products. Are you satisfied with it? Would you recommend it to those who are just starting out?

Marco: Absolutely, but don't expect it to be a solution to all your problems. We like working with them, but it’s a full time job. Creating the products, photographing them, describing them, calculating shipping costs to all countries around the world, advertising, ensuring we appear at the top of Etsy search results – it all requires hours upon hours of work, as well as will to learn and commitment. I hate the whole marketing part of our work, because of a previous work experience. Yet I must say that, when it comes to selling our stuff it's less stressing for me to spend my evening hours studying ways to improve our marketing."

From production to photographing the product to shipping it. Then come accounting work, promotion and business relations. You also offer courses in lathing and maintain a farm. What is your secret for being able to handle all this by yourselves?

Marco: "First of all, there are the two of us. This means dividing the profits but also the workload. Above all, however, the secret (which Pulcinella couldn't keep) is to resign ourselves to the idea of possibly not making it. Get used to the idea that if you set yourself 10 goals, you will not be able to achieve all of them on time. Don't let stress build up and ruin your stomach. Just keep calm and go on. This is our biggest problem and our biggest challenge in 2018. Carry on with our lives, do sports, read books and get together with friends. Because it's so easy to let yourself drown in a negative vortex telling yourself "I haven't done enough, I should've done more", and then find yourself 10 years later an older man with little money in your pocket and with nothing else of true value. We left the city and came to live in the country in order to live a slower life, and that's what we intend to do. This means no work on Sundays, even when we're late with our work. Remembering always that we're just a couple of artisans who produce art objects. Real life is made of relationships, experience, sensations, thoughts and ideas. If you keep this attitude, you can breathe more easily and take life as it comes. Often, in the end, it doesn't turn out too bad at all."

How do you explain the fact that your products are sold mainly abroad? Can you make a living with such a defined market?

Marco: "Given that we've left the city, minimised our living expenses (wood heating, no television, rarely going out at night, cultivating vegetables and fruits to cut shopping costs, etc.), I can say that we live well and, at the moment, making a pretty good living. We didn't strike it rich, if that's what you ask. We're doing okay. But considering we started from zero 3 years ago, 2017 ended up positive. For us this a great success. I believe we sell more abroad due to Etsy's internal dynamics: products are better promoted in markets where they sell more. Or perhaps it is because the first product we sold in America was an olive wood chopping board. But, frankly, I don’t know. What is certain is that abroad, ordinary people who go to shop in markets can easily distinguish a product of high craftsmanship, because they have seen such products around since childhood, as boy scouts, in church, in marketplaces, etc. They understand the work put into such products and therefore accept their price, willing to spend any sum they consider appropriate. In Italy, from what I've seen during my three year experience (not very long, I admit), most people can no longer tell the difference between high and low levels of craftsmanship. There is confusion over the fact that a company that produces 5,000 pieces a day is an artisan producer. For a long time now (two or three generations, I'd say) you rarely find an artisan working in his or her shop. That's why there are few people who understand the work and costs that went into making each product. Not because we Italians are ignorant, or anything like that. It is simply because artisans have been fighting extinction for generations and most people have never seen a plate being lathed or iron being beaten. It is obvious, then, why we can't appreciate items we see on display in artisan marketplaces. This could possibly explain why it's easier to sell abroad. I speak for ourselves only, however. I wouldn't dream, of course, of generalising and saying that this is true for everybody."

Bianca & Sons

Wood, clay and a dog in the countryside of Italy

biancaandsons.weebly.com

Fill out the online form to be contacted by a salesperson